“Perhaps my best years are gone. When there was a chance of happiness. But I wouldn’t want them back. Not with the fire in me now. No, I wouldn’t want them back.” – Krapp

In the era of COVID-19, most, if not all people can relate to the feeling of having had irreplaceable time stolen from them. As if in response to this widespread loss, Richmond’s Firehouse Theatre recently featured socially-distanced, intimate showings of Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, breathing new meaning into the 1958 one-act drama.

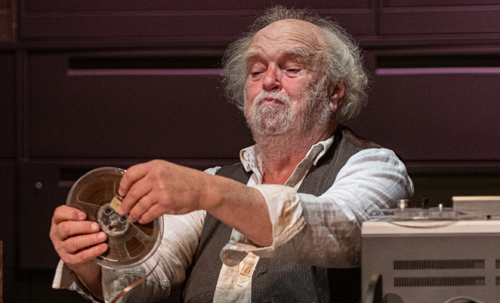

As an attention-demanding clock ticks on in the background, Krapp hobbles onstage to offer the audience a glimpse of his most time-honored birthday tradition. Veteran thespian, Alan Sader, channels the doddering, 69-year-old loner as he moves heaven and earth in hopes of hearing the birthday tapes he’d recorded in years gone by. As he shakily ascended the set’s towering filing cabinet facades, I found myself gripped by anticipation and unease as each step presented an increasingly dire fall risk for the frail and declining Krapp. Without a single word spoken until around the twenty-five-minute mark, Sader relied on physical comedy and timely interactions with the set to maintain audience engagement. Once the more harrowing tasks were completed and the tapes began to roll, the full effect of the sole performer’s deteriorating, disenchanted, banana-obsessed Krapp finally washed over the crowd.

Under the low, commanding light of the lamp above his desk, Krapp reminisced, listening to various birthday tape recordings from years long past. As I gauged his every reaction to the words of his younger self, the character was reinvented before my eyes. What Sader originally presented as an old drunkard fighting a losing battle against the grips of senility, I began to see as a vexingly complex character coping with everything from missed opportunities to the unrelenting march of time itself. This sense of engagement never ceased, as Krapp indirectly invited me to consider whether I had been more affected by every opportunity I had taken in my life, or by every opportunity I hadn’t.

This isn’t the kind of production I usually go out for. It was the first one-man show I’ve ever attended, and I had no idea what to expect. I’d previously read the play for a class assignment in my sophomore year, however, seeing it in the flesh required me to throw away everything I thought I knew. Firehouse Theatre’s dedicated production team brilliantly played into the intimacy of the narrative, creating an ambience that brought the small audience that much closer to the story. My appreciation for the life that Sader brought to his character is matched only by respect for the producers that helped him so fully become the confounding Krapp. Efficient spatial decisions from Production Designer Todd Labelle assured that Firehouse’s compact stage could comfortably house the dim, solitary setting of Krapp’s office. Likewise, Costume and Sound Designers Colin Lowrey and James Ricks (who also wore the cap of Director), along with Vocal Consultant Erica Hughes, made certain that Sader’s look and sound were in perfect alignment with their vision for the production.

Director James Ricks’s notes on the production posit that author Samuel Beckett “made a pretty successful career out of calling our attention to the absurdity of it all.” What better play to put on in a time where the absurd has become a mainstay? In every ragged breath and fatigued movement Krapp undertook, we were reminded of the objectionable, yet nonnegotiable movement of time. And though we may look back on this grievous era with disdain and regret someday down the line, we might also remember the lengths that a small Richmond theater went to to ensure that a select few could safely enjoy an all-too-brief, inexpressibly refreshing artistic experience.